In 2014, Gilead Sciences launched "Sofosbuvir" in the EU as a new drug, which at that time and still today is the best therapy regime for the treatment of hepatitis C. For example, in combination with daclatasvir as another active ingredient, a complete cure can be achieved in over 95 percent of patients after twelve weeks of therapy. This drug, aroused a relatively strong controversy at the time, as the manufacturer had acquired the rights to use the drug by taking over the much smaller company Pharmasset, which originally developed the active ingredient, and the drug was initially marketed at an entry price of about €700 per tablet and total treatment costs for a treatment of 12 weeks of about €60,000. Here, the public perceived a significant disproportion between the production and development costs of the active ingredient (some €100 per treatment) and the price which the manufacturer did ask for. It is therefore not surprising that a number of competitors, but also the organization Mediciens du Monde, filed an opposition against the patent on this active ingredient.

On this opposition, the EPO Board of Appeal has now issued a "provisional" decision, according to which the patent can be maintained in a slightly amended form. This decision deals with two points which we believe are instructive for understanding the EPO's assessment of the requirements of disclosure and inventive step:

The first point concerns amendments in the examination procedure (Art. 123 EPC), for which the EPO requires direct and unambiguous disclosure. In the patent in question, the patentee had introduced two new dependent claims in the course of the examination, which relate to individual enantiomers (i.e. compounds differing only in spatial arrangement of substituents, but not in the structural formula) of the compound claimed in claim 1. In doing so, he had relied on the structural formula describing the racemate (50:50 mixture) of these enantiomers. In this respect, every chemist knows that a racemate is a mixture of the two enantiomers, and it was also described in the application that racemates of the compounds described in the application could be separated by chromatographic methods. However, since the original application described a large variety of chemical compounds, and the enantiomers of the molecules indicated in the dependent claims were not disclosed as such in the application, the Board of Appeal did not consider this description to be sufficient within the meaning of Art. 123(2) EPC. This shows once again that the EPO applies a photographic concept of disclosure in which something, which is not clearly described, is not considered to be disclosed in accordance with Art. 123 EPC.

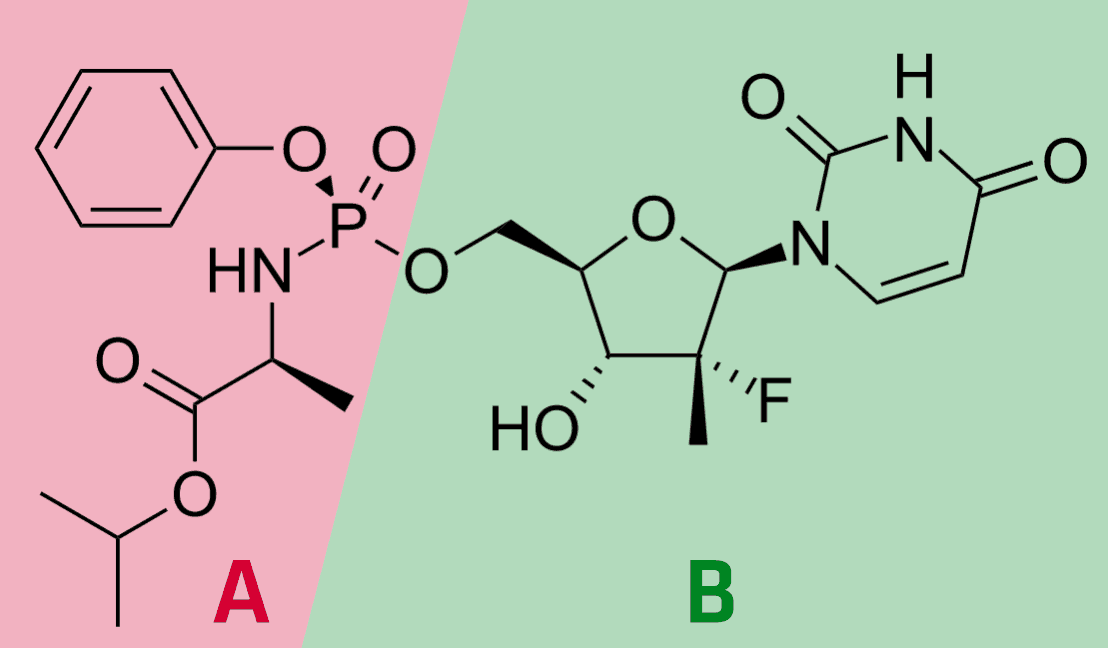

In the second part of the decision, the Board of Appeal dealt more intensively with the inventive step, and in particular with the question under which circumstances the assessment of this requirement can be influenced by hindsight. For inventive step, the opponents had started from several documents in which the activity of the compound with structure B above against hepatitis C viruses had been investigated. These documents were combined with prior art in which the activation of initially inactive compounds by addition of an aryl phosphoramidate (A above) was described. Among other things, such modification was intended to improve cell membrane permeation so that the compound could better enter the infected cell. The motivation for such a modification was deemed to arise from the fact that the unmodified form was not effective against hepatitis C.

The Board of Appeal did not find this argumentation convincing because the information on the non-efficacy of "compound B" was not disclosed in the prior art on which the opponents had relied, but had to be taken from another document. Therefore, the Board of Appeal saw no pointer for such a modification from the closest prior art or from the prior art that could have suggested the modification. In order to arrive at the solution according to the patent, the skilled person would have had to recognize that the closest prior art compound was not sufficiently active by means of a further document, and would then have to realize that the modification described in the further prior art could improve the activity. Such a two-step cognitive process was seen by the board of appeal as the result of hindsight.

The decision of the Board of Appeal is not yet final because an issue relating to the priority that was claimed by the patent had been raised in the opposition. In this regard, submissions G 2/21 and G 1/22 are currently pending before the Enlarged Board of Appeal, so that the further proceedings in T 2643/16 have been suspended until this decision has been issued. However, if the Enlarged Board of Appeal will eventually recognize the validity of claiming a priority under the circumstances given in T 2643/16, the patent can be expected to be maintained in the scope of the granted claim 1. Due to the extraordinarily high value of the patent, the final outcome of the appeal proceedings may be eagerly awaited.